Dr. Bonnie J. Schupp, retired educator, taught in Baltimore City, Annapolis and Pasadena, Maryland.

|

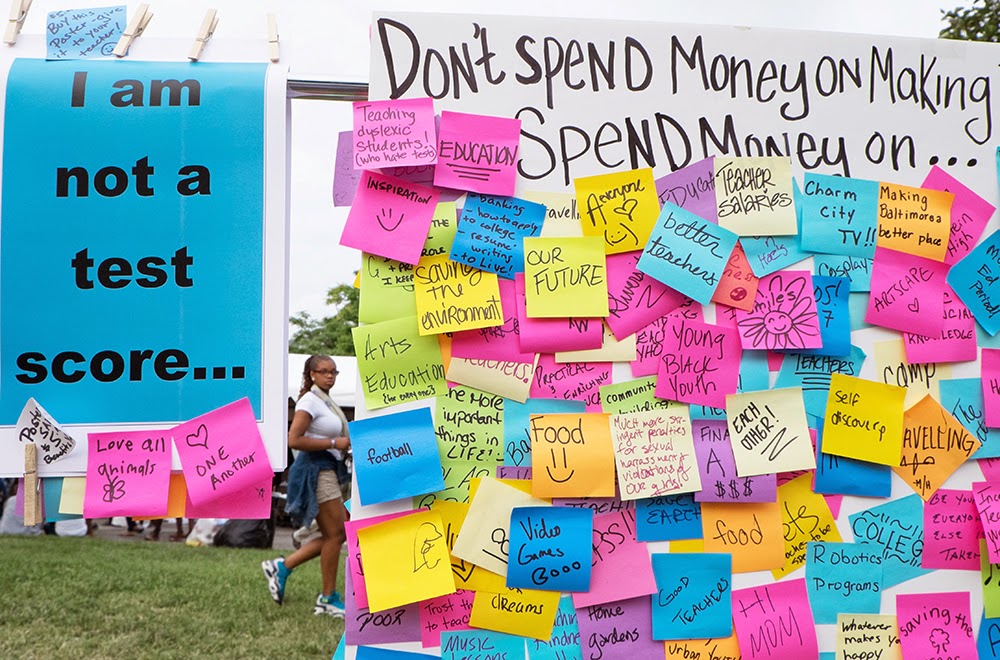

| Youth Dreamers display at Artscape © Bonnie J. Schupp 2014 |

Trends come and go

Sadly, our culture has become

one with short-attention spans spurred on by technology of limited character

tweets and television styles catering to a focus limit of 1 ½ minutes. I

see this in the field of education also with policy makers. Every 5-10 years a

new educational trend explodes—and then disappears quietly. Remember those

students who were not taught phonics but rather whole language alone? Remember

learning centers? Remember cooperative learning, the comprehensive (bigger)

high school model, A Nation at Risk Effective Schools, Madeline Hunter’s SPONGE,

Standards Based Education, and schools within schools? Now we have Common Core. There has always been

and will always be endless streams of new initiatives in public schools.

By the time I left education, teachers had to write

the class objective (in educational terms) daily on the board, students read it

at the beginning of the class and then repeated what they learned at the end of

class. Just before I retired in 2003 to complete work on my doctorate, another

disturbing trend was on the horizon. Middle school students did not understand

how damaging a zero could be to their average. (Every year I always spent a half hour

at the beginning of school doing math with my students to show what happens.) According to the school system,

the solution was that teachers could not give a grade below 50 to students,

even when they failed to do the work. Needless to say, a subtle negative message goes out to students when they get credit for doing no work.

Those who lead education

always seem to be wearing blinders. They see in a narrow and shallow way that

limits their understanding of the breadth and depth needed to educate children.

Contrary to Bush’s No Child

Left Behind (NCLB) and Obama’s Race to the Top, there are no quick fixes in

education. It is incredible that so many people believe that we merely have to

raise standardized test scores by a certain date and everything will be okay.

Even more incredible, they believe that teachers bear all responsibility for

fixing things and that they should be rewarded or punished based on the test

scores of their students.

(Read this humorous piece about what would happen if we held dentists responsible for their patients' cavities: http://bloomingjourney.blogspot.com/2002/02/httpwww.html )

(Read this humorous piece about what would happen if we held dentists responsible for their patients' cavities: http://bloomingjourney.blogspot.com/2002/02/httpwww.html )

There is no shortage of

articles and books about what is wrong with American public schools and I will

include links at the end of this blog. Bottom line is that trends come and go,

many fail, and our students could be more successful if teachers were just

allowed to teach.

Today, standardized tests are

driving curriculum and our children are the losers. When I won a Fulbright Memorial Teachers Fund trip to Japan and

visited classrooms there, I saw the effects of a test-driven curriculum. Japanese students were tested only on reading and writing in their English

classes. Since spoken English was not tested, they were not taught much spoken

English. Even some of their teachers could not speak much English. It is

interesting that Japan and the United States seem to be switching approaches to

education these days. We are focusing on tests while they are changing focus to

the whole child.

Teaching before the test worship

I am disturbed about the

trend to eliminate certain subjects that do not relate directly to the tests.

People who are not teachers and who are driving education reform do not see the

big picture. School subjects overlap and reinforce one another. For example, one

of the novels I taught in 7th grade was The Cay by Theodore Taylor. These are just of few of the skills and

concepts I covered, often skills that are focused on in other subjects:

- Reading and drawing maps; creating and interpreting symbols

- History – World War II

- Global cultures

- Cause and effect

- Point-of-view

- Empathy

- Finding patterns

- Summarizing

- Vocabulary

- Connotation and denotation

- Meaning in context

- Survival skills; prioritizing

- Weather

- Punctuation

- Music

- Main idea and supporting details

- Predicting

- Figurative language

- Inference

- Connection between setting and characters

- Story structure

- Dialect

- Multiculturalism

- Reasoning

When we completed our study,

the elements of Bloom’s taxonomy (knowledge, understanding,

application, analysis, synthesis, evaluation) had been incorporated into student

learning. My students received an education with breadth and depth.

The newest educational trend today is Common Core. I have no problem with

setting standards, benchmarks of learning for each grade. However, as usual in

education, a good idea becomes distorted when it is implemented. There is a lack

of emphasis on social studies and science. Common Core language arts lessons are

structured for each day of a six-week unit. On paper, some of it looks

good. In practice, there are glitches—special student needs, fire drills,

absences, classroom fights, special school functions and more. I may be wrong,

but it appears to be strictly scripted with little flexibility for spontaneity

and creativity that promise to connect students with learning in meaningful

ways.

How does testing hurt our children’s education?

This answer was clear to me

close to the end of my teaching career. We teachers had to teach for the tests. When I began teaching in 1967, I floundered

the first year and then, with practice, became a better teacher. After teaching

in Baltimore City, Annapolis and finally in Pasadena (Maryland), I had become a

more effective teacher than when I started, but by the time I retired, I had no

time to put my skills into practice. The joy of teaching had been replaced with

teaching for standardized tests.

|

| Youth Dreamers display at Artscape © Bonnie J. Schupp 2014 |

This test focus results in:

- loss of in-depth instructional time in the class

- removal of curriculum/classes that are not part of the testing program

- millions of dollars spent on testing when that money could be more effectively used for real education

- loss of the joy of learning

- misleading assessments of learning

- teaching children to be good test takers rather than educating them

- the belief that test scores tell all

When teaching was fun and successful

Before the testing craze, I

taught a unit on heroes, which was part of the 7th grade curriculum.

It involved teaching reading and writing skills through literature, non-fiction

and fiction. The first lesson involved trying together to define what a hero

was. Such a fun lesson. My students read stories of real-life heroes from all

cultures. I used newspaper articles. Through role-playing, I introduced the good Samaritan concept and shared a Scholastic Scope article for which I had taken the photo many years ago. It was about an inner-city youth who might

have been considered a good Samaritan, maybe a hero. http://bonnieschupp.com/Victor.jpg

One of the available novels

for this unit was an age-appropriate version of Beowulf. It offered a platform

for teaching many reading and writing skills and some great thinking skills

too. Good versus evil. Monsters. Bloody fights. These things captured my middle

school students but there were many subtle things that I taught. Students were

saying, “Yea, Grendel, the mean monster was killed.” We could look at the issue

of bullying. We could also address empathy when Grendel’s mother took revenge for

her monster son’s murder. We discussed how she must have felt and students had

to write a piece from the mother’s perspective. One of my 7th-grade

students (he had failed twice and should have been in 9th grade)

told me that this was the first book in his life that he had ever read through to the end.

“Tell me a fact and I’ll learn. Tell me the truth and I’ll believe. But tell me a story and it will live in my heart forever.”—Indian Proverb

Also, with this unit, my students

produced original books. I divided them into carefully selected groups, keeping

in mind each student’s strengths and weaknesses. I gave them specific

instruction as to what elements had to be in this book: a story of a hero who

fit into the definition of a hero that we had come up with, illustrations, bios

of the students in the group who produced this book, etc. When they finished, group members received copies of their book. It was a lot of

work as a teacher—and an exhausting process—but I did it because I witnessed my

students’ enthusiasm as they learned and grew.

Years later, when teaching

for the test mandated that I drop this activity, a young man approached me at back-to-school night.

“Hi, Ms. Schupp, do you remember

me?”

From the beginning of 7th-grade

to the end, students change so much that they often look like different

children. It had been several years

since I had taught him.

“You look a lot different

now. I’m going to need some help.”

“John _____. Ms. Schupp, your

class was my favorite.”

Yes, I remembered him. His

attendance record had been poor and led to his failure in my class. Yet, my

class had been his favorite?

“I’m glad to hear that. Why

was it your favorite?”

“Remember those books we made

in your class? Well, I still keep it in my room and read it now and then.”

In today’s punish-the-teacher-for-student-failure culture, I would be considered a bad teacher. After all,

this student (who seldom came to school) had failed my class. However, my class

had been his favorite and I succeeded in making him proud of one of his

accomplishments. This is only one thing that standardized test scores do not

measure.

Also, along with this heroes

unit, the other 7th-grade language arts teacher and I included a

medieval feast day because we had read about King Arthur in a historical setting.

Students were assigned research topics to help them prepare for this special

day: medieval clothing, food, games, beliefs, customs, castles, music.

Then on the big day, during each class period, we met in the “banquet hall”

(the school’s multi-purpose room), did role-playing with royalty, jesters, costumes,

food, music, games. We usually had more parents who helped with this event

than who showed up on parent conference day. Educational? Yes. A success? Yes,

on many levels.

When testing became the

focus, there was no longer time for this event.

|

| Youth Dreamers display at Artscape © Bonnie J. Schupp 2014 |

The trouble with tests

Besides being limited in what

can be assessed, test culture takes money away from other areas that

count. Testing is a moneymaking industry: producing tests, tutoring, testing

services, new textbooks and more.

Tests do not give a complete

and accurate picture and they are not used effectively. Furthermore, students are not held

accountable. The tests aim at basic functional skills while we should be aiming

higher. Most are given during the school year with results coming back so late

that current teachers have no time to respond to them in instruction. They do

not take into account student motivation. I observed close hand how my students

responded to these tests and many put in little or no effort. Middle school

student thinking is askew at that age. Some who dislike their teacher will

actually make no attempt to do well so they can “get back” at their teacher. After

all, students have no consequences for their test scores.

Parents also have no

consequences. Some 12-year-olds get themselves up and “ready” for school. Some

parents have no parenting skills. I have observed parents picking their

children up from school, smoking, and handing over a cigarette to their

children. Sometimes, parents would show up at school to continue fights their

children got into with other children. In some cases, education is devalued. In

the middle of the school year, parents take their children to Disney World for

a week at a time. Never mind that important skills are being taught in class

that week. They ask teachers to send home worksheets a week ahead so, between

Space Mountain and Jungle Cruise, their children can quickly fill in answers.

Teachers should never be

rewarded or punished based on student test scores. Although a teacher is

important, there are too many other factors that play a part.

Learning the buttons but not getting it

In photography, a person can

learn all the buttons on the camera, navigate the digital menu with skill, take

a perfectly sharp and exposed photo, ace a photography test BUT still be a

mediocre or poor photographer.

Education, whether it is

learning how to take photos or learning school subjects such as math, English,

social studies or science, is about more than learning facts. These isolated

facts must be connected with living and all the emotional layers that make up

life. They must connect with communication with yourself, your world and

others. If education does not venture into these less obvious areas, it is a

skeleton with no place to go except the grave.

A certain spirit must drive

true education.

No instant gratification

Learning is a long and

difficult process with incremental improvements over many years. It is

complicated and lives in many layers.

Problems in education cannot be fixed in one or even in five years. Some

shallow thinkers believe we can reward and punish teachers and student test

scores will go up. Not everything is based on teachers’ skills. The education

of a child is complicated and solutions are multi-faceted.

Students do not come to the

classroom as empty vessels ready to be filled with knowledge. They bring a lot

of baggage with them. There are issues of poverty, housing, unemployment,

health needs, social problems, dysfunctional families. They come to school at

many levels regarding family attitude and support toward education.

The blame for problems in

education does not lie with any one group of people or one thing: teachers,

administrators, students, parents, society. We have to stop over-simplifying the problem

and trying to fix it by focusing on only one area or assessing with only one

tool. This reminds me of the adage: If

the only tool you have is a hammer, then all your problems will look like

nails.

And we have to stop believing

that non-educators know the answers.

Solution: Class size IS important

Bill Gates has said that

class size does not matter. He is wrong! Consider the math in a language arts

teacher’s life. If I have 30 students

for 50 minutes, that leaves just a little more than a minute to give individual

attention to each student in my room. It also means that if I give a writing

assignment and spend five minutes assessing it for each of my 150 students

(five classes each day), then I will spend 12 ½ hours grading only one assignment,

one practice test. That is beside planning lessons, parent conferences,

graduate classes at night and trying to have a personal family life. Bill Gates

may have made a lot of money but any underpaid teacher knows that he does not

know what he is talking about when he says that class size does not matter. He

may be a good businessman, but he is no educator.

(p. 275) In 2010, Gates advised the National Governors Association that states could save money by not paying extra for advanced degrees or experience and by increasing class size for the best teachers, the ones whose students get higher test scores. He stated that the ‘evidence’ showed that seniority seemed to have no effect on student achievement after a teacher’s first few years. He did not explain how American education would get better if teachers had less education, less experience, and larger classes.” (The Death and Life of the Great American School System: How Testing and Choice are Undermining Education, by Diane Ravitch)

Teaching conditions and climate are more important to some teachers than pay, although paying professional teachers well would show that society values them, maybe not as much as famous sports figures though. Teachers need to feel effective and appreciated. They need to feel empowered.

Solution: A multi-faceted approach is important

To improve education, we have

to stop listening to policy makers who do not know the answers and begin to

look at a broad spectrum of issues from the bottom-up. The local school community—parents, teachers,

students—must all be involved. The homes that students come from need to be

considered and social services offered, counseling, education, mentors. We must listen to the voices of teachers who

can do a better job with small classes, teaching assistants, and a strong curriculum not driven by tests. School systems need to recognize that teaching for the tests

hurts students’ education by devaluing other subjects, by taking up too much

time that could be used for real teaching and by providing a distorted

assessment.

Subjects other than language

arts and math are also important. Excellent teacher training in college should

include mandatory internship as student teachers. First-year teachers need the

support of mentors. School systems need to include experienced teachers in

policy-making.

Change must come from the

bottom-up. So far, it has failed from the top-down.

Let's not be distracted by the false data god.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

(Photos taken at Baltimore's Artscape. More information about the post-it note inspiration here: http://www.youthdreamers.org/pages/book.html)

P.S. I just read a most interesting essay written by a parent: An Open Letter to My Son's Kindergarten Teacher.

It is worth reading!https://medium.com/teaching-learning/an-open-letter-to-my-sons-kindergarten-teacher-ed1f90239ae7

Read Part 2

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

More of my writing on education:

Creativity and Education - http://bjschupp.blogspot.com/2009/05/creativity-and-arts-in-classroom.html

Creativity – AVAM http://bjschupp.blogspot.com/2009/05/creativity-part-i.html

Size Matters - http://bjschupp.blogspot.com/2010/12/size-matters.html

Linking Teacher Pay to Student Performance - http://bjschupp.blogspot.com/2011/07/linking-teacher-pay-to-student.html

American

Visionary Art Museum's Educational Goals

Other reading of interest:

Time Magazine, July 28, 2014, Why the Common Core Can Never Do What Ed Reformers Claim

It Will

http://tinyurl.com/lgwonz4

Dianne Ravitch on Common Core: http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/answer-sheet/wp/2014/01/18/everything-you-need-to-know-about-common-core-ravitch/

http://www.forbes.com/sites/ashoka/2013/02/15/how-should-we-rebuild-the-u-s-education-system/

No comments:

Post a Comment

This space for your comments: